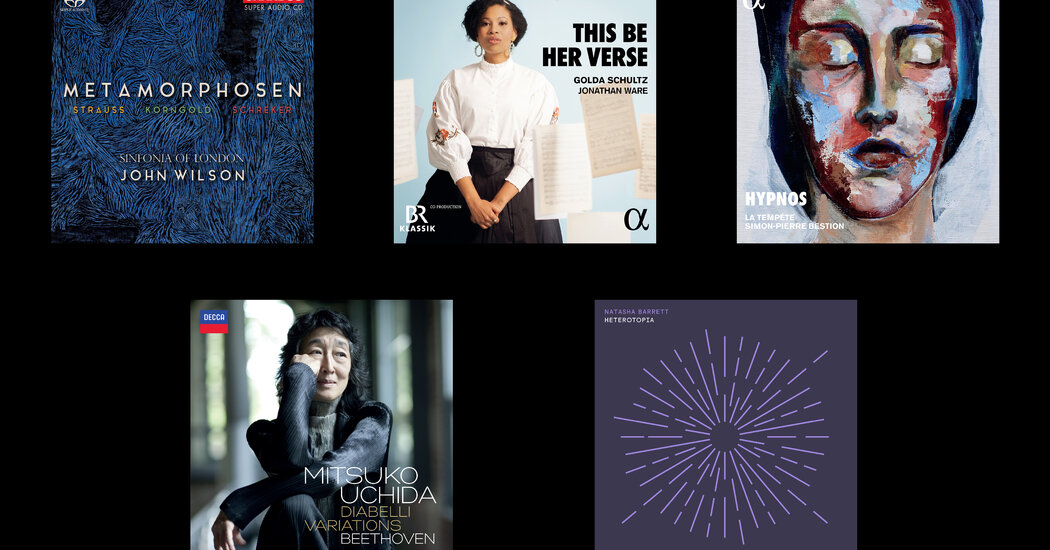

Beethoven: ‘Diabelli’ Variations

Mitsuko Uchida, piano (Decca)

Slowly, slowly, Mitsuko Uchida adds to her Beethoven discography — these “Diabelli” Variations now joining her five sonatas and two surveys of the piano concertos, with Kurt Sanderling and Simon Rattle.

Her latest is worth the wait.

There are pianists who will tell you that the “Diabellis” have to be funny, who play them as if they were slight — a diversion. Not Uchida. She renders each of Beethoven’s 33 transformations of the title theme with the fastidious precision she has brought to Schoenberg and Webern. Listen to the second variation, and how her fingers seem to have leaped from the keys even before they have been pressed; or to the ease of the washing figures of the eighth, hardly far from Debussy; or to the telling way that she voices the chords in the 20th and 28th. Some of the variations even take on the intensity and drama of little sonatas; how extreme she makes the contrasts of the 13th, and how inevitable her resolution of them feels.

Uchida never leaves you in any doubt that this is a late work, with glimpses of the sublime — apt, really, from this most sublime of pianists. DAVID ALLEN

‘This Be Her Verse’

Golda Schultz, soprano; Jonathan Ware, piano (Alpha)

Nearly five years ago, in her Metropolitan Opera debut, the soprano Golda Schultz had a tone by turns light and lush, showing signs of promise that since have been borne out with aching optimism in “Porgy and Bess”; playful charisma in show tunes; flowing elegance in “Der Freischütz”; and more.

Schultz is putting her gifts to good use. Having built a career in a male-dominated canon, in this album, recorded with the pianist Jonathan Ware, she programs only works by women. Sometimes those in the shadow of men: Clara Schumann, for example, who largely gave up composing after she married Robert Schumann, and who here has a setting of “Liebst du um Schönheit” less famous as Mahler’s in “Rückert-Lieder.” A similar story follows Emilie Mayer, a Romantic whose “Erlkönig” is obscure compared with that of Schubert.

Such programming offers a shift in perspective. Clara Schumann writes with a loveliness that Mahler underscores with an anxious darkness; Mayer’s “Erlkönig” churns with drama, but with more shape than Schubert’s hellfire. Ware brings a theatrical sensibility to that song, matching Schultz’s ease as an art song raconteur, as in Rebecca Clarke’s “The Seal Man.”

Schultz isn’t always so comfortable, with an effortful lower range in Schumann’s “Am Strande.” But at her best, she sings with lustrous delicacy — soaring in Nadia Boulanger’s “Prière” and rending in Clarke’s “Down by the Salley Gardens” — and operatic urgency. Naturally, the finest fit is Kathleen Tagg’s “This be her verse,” a commission for the program that, in addition to strummed piano strings, calls for suspended, ethereal high notes and carefree charm. JOSHUA BARONE

‘Hypnos’

La Tempête; Simon-Pierre Bestion, director (Alpha)

This dreamy album’s title invokes the Greek personification of sleep, and its lushness in repertory, stretching from the Middle Ages to the late 20th century, indeed approaches the narcotic. But while I was expecting the track list to include more explicit references to slumber — like the “sommeils,” or sleeping scenes, that the French Baroque borrowed from earlier Venetian opera — the recording’s content, heavy on requiems and elegies, draws more from Hypnos’s twin brother, Thanatos, the embodiment of death.

That blurring of nocturne and eulogy is intentional: Simon-Pierre Bestion, who founded the ensemble La Tempête in 2015 and leads it in remarkably creative programs, is after a (yes) hypnotic homogeneity here, a night that feels as endless as the grave. With a mellow undercurrent of just cornet and bass clarinet, the 10 singers are ritualistically rapt as they glide through works by Pierre de Manchicourt, Ludwig Senfl, Pedro de Escobar, Marbrianus de Orto, Antoine de Févin and Juan de Anchieta. There is also Heinrich Isaac’s “Quis dabit capiti meo aquam,” a spectacular highlight; keening chants from medieval Rome and Milan; and haunting modern pieces by Olivier Greif (from his Requiem, with its eerie quotation of the lullaby “Hush, Little Baby”), Giacinto Scelsi, Marcel Pérès and John Tavener, all wholly at home in these stupefacient surroundings. ZACHARY WOOLFE

Natasha Barrett: ‘Heterotopia’

(Persistence of Sound)

It’s easy to get caught up in technical details when talking about Natasha Barrett’s work. She uses ambisonics to compose and mix music in 3-D formats. Some of her live performances — such as at Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center (EMPAC) in Troy, N.Y. — use dozens of speakers arrayed around an audience in a precise dome that could intimidate an IMAX theater’s sound system.

But what use is all of that at home? Not much, Barrett has recognized. While some of her releases use binaural mixing — in an attempt to get that immersive, spatial sound to work over a pair of headphones — she’s also game to produce a more typical mix of her work. That’s the case with “Heterotopia,” whose title track is a reference to Foucault’s idea of otherness. You don’t need a complex setup to get into it; just fire up your best speakers and press play.

The nine-minute “Urban Melt in Park Palais Meran” begins as a field recording of an amiable outdoor table tennis match. But within the first minutes, you can feel the plink-plonking tones entering into a sonic multiverse — splitting apart, doubling, with different iterations of the game cascading over one another. This works well in a space with dozens of speakers, like EMPAC. But Barrett’s overall conception of the piece — with the audio documentary feel giving way to passages strewn with resonant drones and whipping, trebly textures — makes for compelling drama when heard in stereo, too. SETH COLTER WALLS

‘Metamorphosen’

Sinfonia of London; John Wilson, conductor (Chandos)

What a fine and stimulating recording this is. The Sinfonia of London is a session ensemble of leading players who record and perform under the baton of John Wilson, a brilliantly talented Englishman who sees no good reason to stick to concert music; he came to prominence playing Broadway classics and film music of old. And if his orchestra’s name sounds familiar, so it might. Fitfully in use since the 1950s, it was the title of the ensemble that played on John Barbirolli’s 1963 record of string music by Elgar and Vaughan Williams. And perhaps nobody since Barbirolli has been able to make strings sing like Wilson; Schreker’s “Intermezzo” here has a sheen to it that is intensely delicate one minute and impossibly sumptuous the next.

The rest of this recording offers divergent responses to the place of tradition at the end of World War II, questioning of the fate of exactly the kind of late Romantic music Wilson cherishes. Strauss’s “Metamorphosen” has rarely had such an agonizingly drawn out, lovingly burnished performance as this. Even better is the rarity that accompanies it: Korngold’s Symphonic Serenade, a disfigured, difficult recollection of all that poignantly easygoing light music in the Austrian tradition, written when he returned to Vienna from Hollywood. The hush that Wilson finds for its slow movement is indescribably haunting. DAVID ALLEN